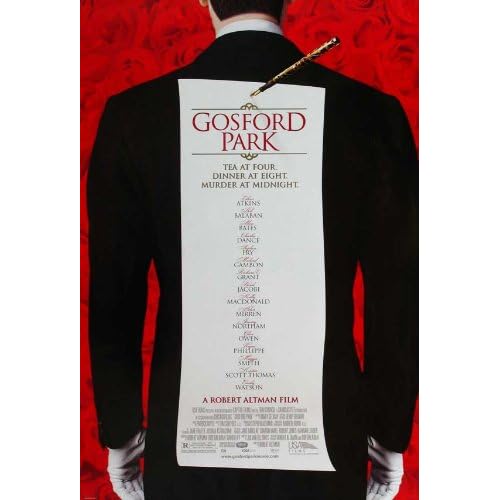

Director: Robert Altman, 2001 (R)

Having

spent the last two months catching up on seasons 1 and 2 of Downton Abbey so

that I could watch the current one in real-time (as much as it is real-time

when viewed on OPB in Oregon even while it has been broadcast in the UK), I am

missing my DA fix. Even with the car wreck of a season that was season 3, that

had its ups and major downs, I still needed some significant

“upstairs-downstairs” action. What better movie to turn to than Robert Altman’s Gosford Park.

After

coming up with the idea for the film, Robert Altman needed a strong

scriptwriter. Bob Balaban, who plays a Hollywood producer in the film,

suggested Julian Fellowes and Altman gave him the opportunity. Fellows, an

average actor, turned in a sizzling screenplay, one that won him an Oscar and

gave him the chance to pen something that was gestational prior to Downton

Abbey, his brainchild almost a decade later.

On

paper the film is an ensemble murder mystery. But it is so much more than this.

It is in part subtle and sarcastic comedy, in other part social commentary. But

the screenplay combined with the quality of the acting makes it a cinematic

feast, even if it is one that is stewed in a slow-cooker.

It is

set in 1932 in a British country manor. The host Sir William McCordie (Michael

Gambon) has invited a number of colleagues, friends and family to a weekend

pheasant shooting party. All the guests seem to want something from him, mostly

money or support. And there is no love lost between most of them, even if they

keep their feelings well under control – the so-called British stiff-upper lip.

The

first hour of the film introduces us to his guests, and there is a long list of

them, including the Hollywood producter and British film star. It is hard to

keep track of the characters, but Altman is known for his ensembles and strives

to include enough pointers to help the viewers. Each of the guests brings his

own “man” or maid, and these socialize and work downstairs alongside Sir

William’s own staff led by butler Mr. Jennings (Alan Bates) and the housekeeper

Mrs. Wilson (Helen Wilson).

The

rich cast is a veritable who’s who of British acting, including Kristin Scott

Thomas as Lady Sylvia McCordie (wife of Sir William), Clive Owen as one valet,

and Emily Watson and Kelly McDonald as two maids. Ryan Phiippe, too, shows up

as another valet. But trumping them all is Maggie Smith as Constance Trentham,

the sister of the host, who is dependent on her brother for her monthly

allowance, an allowance he constantly threatens to terminate. Like her

character on Downton Abbey, she is the queen of the sarcastic put-down remark.

For example, talking to Ivor Novello (Jeremy Northam), the actor, on his recent

film after another character has fawned all over him, she says: “It must be

rather disappointing when something flops like that.” Her barbs are quick and

poisonous, but delivered with a soothing smile. And poison is prominently

featured in the cinematography as it is ever-present below stairs.

The

rich cast is a veritable who’s who of British acting, including Kristin Scott

Thomas as Lady Sylvia McCordie (wife of Sir William), Clive Owen as one valet,

and Emily Watson and Kelly McDonald as two maids. Ryan Phiippe, too, shows up

as another valet. But trumping them all is Maggie Smith as Constance Trentham,

the sister of the host, who is dependent on her brother for her monthly

allowance, an allowance he constantly threatens to terminate. Like her

character on Downton Abbey, she is the queen of the sarcastic put-down remark.

For example, talking to Ivor Novello (Jeremy Northam), the actor, on his recent

film after another character has fawned all over him, she says: “It must be

rather disappointing when something flops like that.” Her barbs are quick and

poisonous, but delivered with a soothing smile. And poison is prominently

featured in the cinematography as it is ever-present below stairs.

After

we have established the situation, Altman throws in a murder mystery for the

second act. After a tense dinner where words are thrown like javelins, the host

is found dead in his study, apparently stabbed through the heart. Few of the

guests grieve; there are too many possible suspects with motive to kill him.

When

Inspector Thomson (Stephen Fry) shows up with his constable, they begin an

investigation with both social classes. But their investigation itself is a

caricature of the social divide. Thomson is a bumbling buffoon, more adept at

talking to the rich while his constable works solidly to uncover clues, clues

that Thomson seems to care less about. But this murder mystery is less about

truly solving the mystery in genre fashion, and more about the situation

itself. Altman does end up revealing the murderer from among the many possible

suspects, all of whom seem to have some deep dark secret that comes out over

the course of the weekend. But the fun is in seeing the characters develop in

context.

When

Inspector Thomson (Stephen Fry) shows up with his constable, they begin an

investigation with both social classes. But their investigation itself is a

caricature of the social divide. Thomson is a bumbling buffoon, more adept at

talking to the rich while his constable works solidly to uncover clues, clues

that Thomson seems to care less about. But this murder mystery is less about

truly solving the mystery in genre fashion, and more about the situation

itself. Altman does end up revealing the murderer from among the many possible

suspects, all of whom seem to have some deep dark secret that comes out over

the course of the weekend. But the fun is in seeing the characters develop in

context.

The

main theme of course is the study of the social class system in effect in

Britain between the wars. The rich and the poor were divided. There was little

middle class at that point, and very few evident here.

Class

structure has been present in cultures since the beginning of time. Earlier

civilizations embraced slavery as well as the poor and the rich. By the time of

the Romans, Jesus said: “The poor you will always have with you” (Matt. 26:11),

pointing to the fact that there will always be a class divide while he does not

return. Even societies that have strived for equality, such as communism, end

up with some segments of the society more equal than others. There always rises

a ruling class, even if they are not called by that name. And as a corollary,

there is always a ruled class, the poor or working class. How far the divide

stretches and how formal it is, determines the effect of the class structure.

In the 1930s, it was large and daunting, proving almost impossible to vault.

Those in the film who are from a middle class background are put down by those

in the upper class.

The

other theme that emerges comes from one of the characters late in the film.

When someone tells her she has sacrificed her life for her master, she

comments: “I’m the perfect servant; I have no life.”

The

other theme that emerges comes from one of the characters late in the film.

When someone tells her she has sacrificed her life for her master, she

comments: “I’m the perfect servant; I have no life.”

This is

a great illustration of biblical truth. Jesus told his followers that they must

serve him (Jn. 12:26). The apostle Paul later said we are all slaves to a

master: we are either slaves to sin (Rom. 6:17) or slaves to God (Rom. 6:22). If

we choose God, which biblically is the preferred choice, we are raised form

slavery to servanthood, and later to friendship (Jn. 15;15) and sonship (Jn.

1:12). Yet, as servants we strive to please God as the perfect servant. And in

Christ, in a sense, we have no life: “I have been crucified with Christ and I

no longer live, but Christ lives in me” (Gal. 2:20). Our new life is a

Christ-life. We are like the character in the film, a perfect servant dedicated

to serving our heavenly master who we also call Father (Matt. 6:9). Where that

person said it in a sad and resigned manner, those of us that choose to follow

Jesus can say it in a joyful and aspirational way.

Copyright ©2013, Martin Baggs

No comments:

Post a Comment